A Brief History of Māori Architecture

And a look into contemporary implementation and significance

When I first came to New Zealand in 2014, I was confronted with new types of architecture that I had never seen before. As someone with zero training in the matter, and (at the time) a somewhat narrow view of what a building could and should be, this was not a big surprise. In hindsight, what ended up becoming interesting was the amount of impact that the buildings had on my way of thinking. What I didn’t realize at the time is that I was most interested by buildings that had a more exotic look about them, and many of these turned out to be influenced by indigenous design languages and concepts. Māori tradition states that a building is a living entity, and that it should be addressed as though it were a person. While this sentiment usually makes more contextual sense when addressing a building of spiritual significance, I feel that it could be applied more broadly to all buildings, as there have been several in my experience that have addressed me.

The Māori traditions and stories pertaining to land and buildings are complex. As a non-indigenous person looking from an outside perspective, I can never fully understand, let alone express the full cultural significance implied. All I can do is use the public information available to me and examine the history around how the Māori used to build their homes and meeting places.

The earliest Māori buildings were based on examples built by their ancestral Polynesian predecessors. Due to the cooler climate of New Zealand these early houses were usually very small with low doors and few window openings which made them much easier to heat. Generally they were made of materials that were light and easy to transport, as tribes would often move around in search of food, medicinal plants, and other materials. Generally, there would be separate sleeping houses for each family in the community, and sometimes a larger meeting building called a wharenui, similar to a longhouse that readers in the US would likely be familiar with. Larger and more sophisticated communities would also have separate buildings for sleeping, food storage, and public gatherings.

Many Māori continued living in villages of this configuration even after contact from European settlers, who (forcibly) attempted to change their way of life to a more “civilized” one that included the European-style cottage house. Some high ranking rangatira (chiefs) were actually early adopters of this European style however, building multi-room houses with chimneys and glazed windows as a sign of their societal prowess. Follow-on effects included the wider implementation of these technologies which were not indigenous by design, but did have some benefits to the health and wellbeing of their occupants, who molded the techniques to suit their traditional lifestyle. Interestingly, the Māori were the only indigenous culture in the Pacific region that implemented a covered front porch into their buildings, a necessity for the wet, temperate environment in which they were situated.

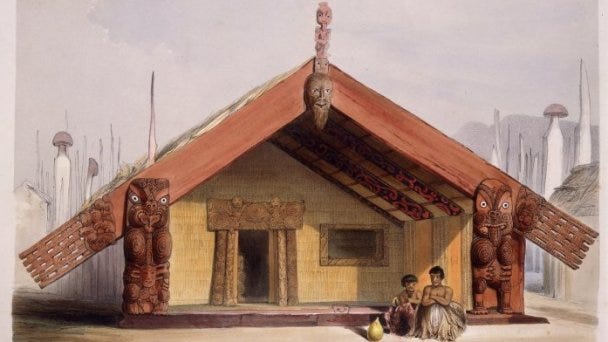

Like the examples pictured above, the whare whakairo has become the most recognizable building associated with the idea of Māori architecture, as they were generally the most unique and suitably adorned. The practice of carving is a key component to Māori buildings, and these meeting places were nearly always intricately decorated with renditions of gods and ancestors of the village. As I mentioned before, the building is seen as an extension of these ancestors, and public proceedings were prefaced with an address to the building itself. It is common practice to build meeting houses facing east, so that they are always exposed to the morning sun, which is seen as a daily renewal.

The evolution of the whare whakairo is a sort of physical embodiment of the ever-changing cultural interactions and associations of the people that build and use them as communal spaces. The Māori believe that a community and its people have an embodied socio-spiritual power called mana whenua. A person or group of people are like a conduit for this spiritual energy that arises from the lands and waterways where they reside, the stewardship of which is a birthright passed down in accordance with their tīpuna (ancestors). The more successful and influential a person or group is, the more mana they embody, giving them more authority over the domain. Kaitiakitanga (guardianship) is of vital importance to improve the physical and spiritual wellbeing of the community. Under the umbrella of stewardship is the idea of restoring and maintaining the local natural environment with the input of the local Iwi (indigenous community), doing so in a way that solidifies the people’s connection to the land.

Even though the physical forms associated with Māori architecture have changed a great deal through contact with European influences, the kaupapa Māori (core values) have remained the same through careful passage down the generations. Many Iwi now exercise their mana to work in conjunction with local governments in their area to ensure new developments fit within these core values, especially with regard to preservation of natural spaces. One such project that caught my eye is a recent proposal to develop a currently unused piece of land near the town center of Paraparaumu where I live. The Kapiti Coast District Council, and the group looking to undertake the actual development are using a Kaitiakitanga Plan developed by the local Iwi that outlines all of the actions that need to happen in order to restore the area to its traditionally useful state.

The aim of this development is to not only reclaim a piece of land that was once inhabited by the local indigenous people, but also create and inclusive space that will create desirable outcomes across the community for generations to come. This land will serve as a “central park for a future city,” one that will arise as the Kapiti Coast becomes more densely populated over time. The enshrinement of this piece of natural history will also serve as a much needed green heart for the city, as well as performing its duty as an active social gathering place for the Iwi, becoming a place where the Māori traditions of gathering and preparing food, medicines, and other natural resources can be continued in a sustainable manner.

The inclusive planning and execution embodied by this project is something that should become the standard practice for all new developing cities. The idea that people will be able to thrive in an environment where the land is artificially manicured and paved over seems shortsighted to me. Humans need a solid connection to nature in order to survive and prosper, something that has increasingly gone missing in modern cities. In this example, the people that are making the most actionable moral contributions are the ones whose ancestors have been inhabitants of this land for centuries, and I find it quite suitable that the centerpiece for the entire project is an architectural form that celebrates the historical and continuing value of indigenous perspectives.

“No matter how exotic human civilization becomes, no matter the developments of life and society nor the complexity of the machine-human interface, there will always come interludes of lonely power when the course of human kind, the very future of humankind, depends upon the relatively simple actions of single individuals.”

- Frank Herbert, Dune: Messiah

References:

Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand - Māori architecture - Whare Māori

https://www.teaomaori.news/history-told-through-whare-whakairo-0

Te Ātiawa ki Whakarongotai Charitable Trust. (2019). KAITIAKITANGA PLAN for TE ĀTIAWA KI WHAKARONGOTAI. Waikanae, NZ; Te Ātiawa ki Whakarongotai Charitable Trust. https://www.whalesong.kiwi/_files/ugd/46f490_4b0e83b1187a409d937537fa2667d2e2.pdf

Kapiti Coast District Council . (2019). Wharemauku House of Ferns - A central park for a future city. Paraparaumu , NZ; Kapiti Coast District Council .

https://kaingaora.govt.nz/assets/Publications/Design-Guidelines/ki-te-hau-kainga-new-perspectives-on-maori-housing-solutions.pdf

Very nice! Love the pictures, and the Frank Herbert quote...