I was born and raised in the Seattle area in the Pacific Northwest of the United States. In this part of North America, we are extremely lucky to have access to a bounty of natural resources, of which the focal point is the Salish Sea. This area encompasses the Puget Sound, the Strait of Juan de Fuca, and the Strait of Georgia, and has coastline throughout most of Western Washington as well as Vancouver Island and British Colombia. This area was also one of the most densely populated by Indigenous and First Peoples in North America, with an estimated population nearing 150,000 prior to contact with European explorers and subsequent settlers. The Salish Sea was home to dozens of different language groups, who lived and thrived there for thousands of years, and it felt right for me to examine the ways in which they achieved this feat without the wholesale obliteration of the marine and terrestrial resources available to them.

Ceremonial Significance

I will again preface this examination with the fact that I am not an Indigenous person, and I can never know the full cultural importance of the topics I will cover here. I am in no way attempting to speak for anyone, nor appropriate any way of life or methodology. The fact is that there is no way to separate the cultural, spiritual, and societal elements from the built environment, as they are effectively one in the same, and thus there can be no discussion of one without the other. I have chosen to take a closer look at this specific genre of buildings purely in the interest of understanding more about the region where I grew up, and the people that have inhabited it since time immemorial.

The Coast Salish peoples, like many other indigenous groups in North America had a very organized and hierarchical structure to their society, all of which revolved around their system of governance called the potlatch. There really is no discussion about Indigenous society without the inclusion of the potlatch, as it was the backbone of how they organized themselves, controlled their resources, and communicated sovereignty amongst their tribal groups and with their neighbors. Unlike many other indigenous groups in the Americas however, Coast Salish people were inherently stationary in their way of life, dissimilar to the plains people, the Sioux for instance, who were generally more nomadic in their ways, following herds of prey animals around the countryside. The main reason for this is the plentiful resources in the lands and waters surrounding them. The Coast Salish people had a heavily maritime-oriented way of life, dependent on fishing, hunting, and gathering in the surrounding areas. One could go so far as to say that these societies were salmon-based economies, where much of the day to day trading was based on the availability of salmon in the seas and rivers.

This more stationary way of life lent itself to the long term habitation of certain sites along the coasts of Western Washington and British Colombia, and eventually gave rise to the largest and longest-standing structures in North America at the time. This also meant that the lands the Indigenous people inhabited had to be carefully managed in order to sustain this larger population over such a long period of time. The potlatch system evolved in a way that guaranteed this, because the wealth and status of a titleholder (chief) was directly related to how much of his bounty he could give away during potlatch meetings. This is a type of governance that is grounded in stewardship, where it was in the best interest of the tribe to keep a chief that knew the most about the historical methods of maintaining the resources of the area. Another way that the potlatch system reinforced sustainable living was that the chief and his successors were required to have a distinct knowledge of their oral histories in order to be eligible for the position. Since the Coast Salish peoples (and most other groups in the Pacific Northwest) had no written languages, these ideas were passed down along the generations in the form of dances, songs, and stories that detailed how certain tribes were socially successful, through the traditional practice of resource management. Additionally, any tribe that fell on hard times could go to their neighbors for support, with the promise of repayment at a later date. Or alternatively, they could determine that the chief had lost his ability to provide for them and have him replaced.

Form and Function

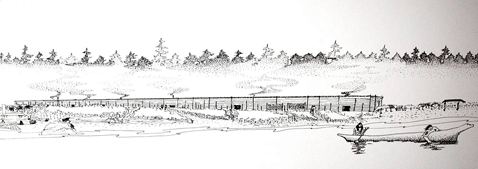

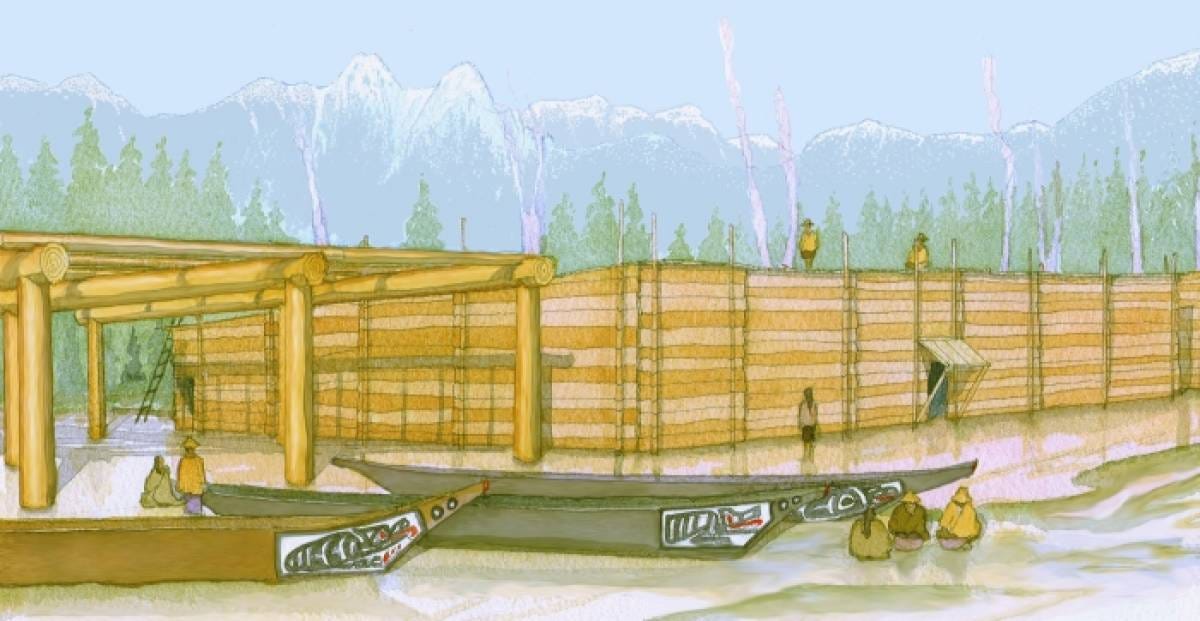

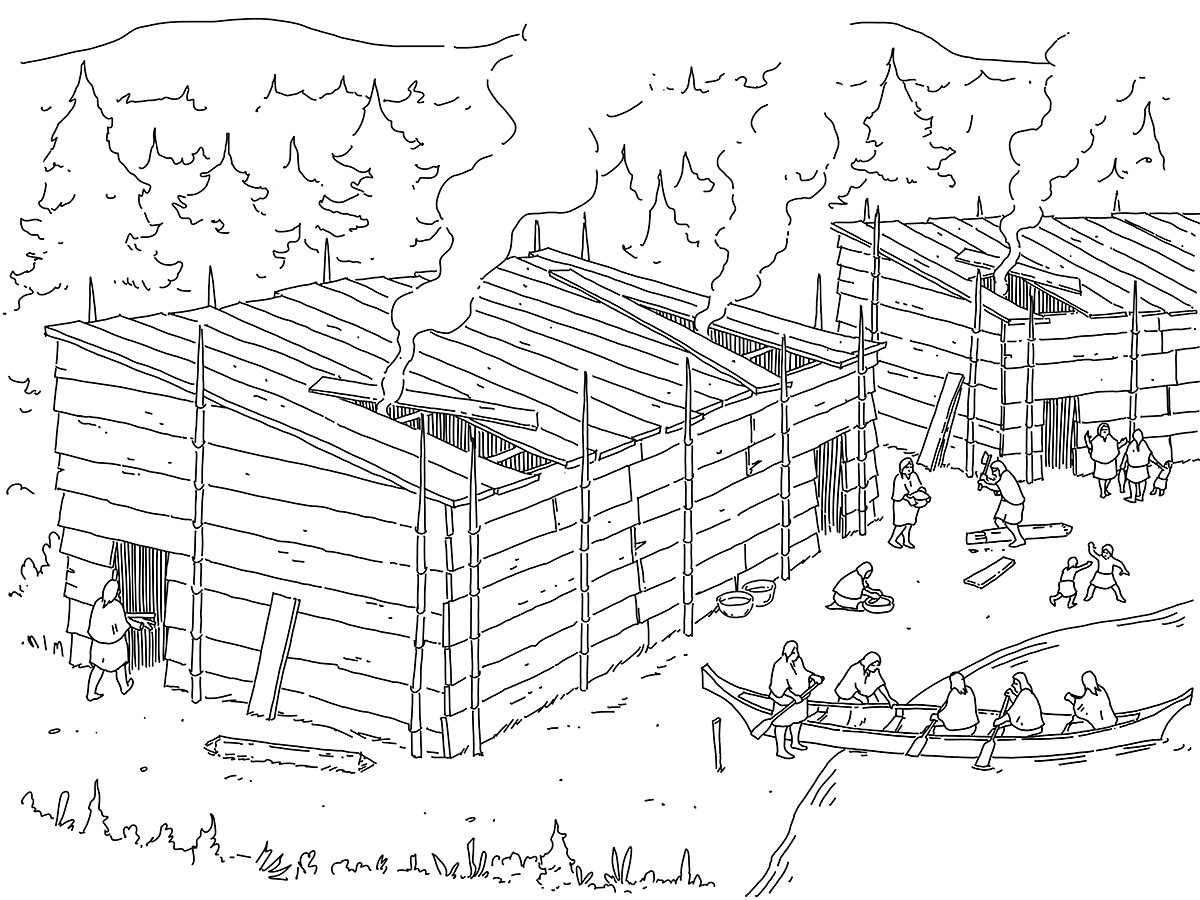

The Coast Salish built a specific type of building that was unique to the area and had very much to do with the materials available for building. At the time, the entire Salish Sea was surrounded by old- growth forests consisting of mainly Western Red Cedar, which was the primary building material they used, along with other local trees and saplings for various other uses. The main form of the buildings were very simple, nearly always a rectangular layout with the longest side facing the water, and a single slope shed style roof, to protect from the rains that characterize the area. Due to the size of trees they had available to them, the Coast Salish used massive cedar posts and beams to create the main frame of the houses, and wide planks to make up the exterior sheathing and roof. There were slight variations in the ways these elements all fit together, but for the most part this was the building formula throughout the region.

One thing I should mention is that the Coast Salish did in fact move their living arrangements in accordance with the seasons. In the summer months, they would remove much of the exterior sheathing and roof planks and carry them on canoes to their summer locations where the fishing and gathering was more plentiful, leaving the massive timber structure intact. In the winter months, they would return to the main village site, and reinstate the walls and roof to the main structure, which would serve as the winter quarters. This is the main reason that the first European explorers thought some areas of the Salish Sea had been abandoned, but what they were actually seeing were the empty winter sites, while the tribes had moved out to their summer locations, which tended to be islands or areas closer to larger bodies of water.

The amount of craftmanship that went into building these structures was immense. Massive trees were felled using fire, adze, and chisels. These trees then had to be dressed in a way that created an equal circumference along the entire length. Posts and beams were notched and carved to interlock with each other. Planks were split from both fallen and standing trees using adzes and wedges. One characteristic of the cedar used was that it had very straight grain which made for easy and even splitting, and the result were fine, long planks, which made up the exterior sheathing. The walls were attached to the main frame using what we could consider a modern curtain wall system, where the planks were lashed to the posts using cord made from cedar bark, which allowed for quick and easy disassembly when it was time to move in the summer. The roof planks were also carved in a very specific manner, very similar to modern roof tiles, with an alternating over-under U-shape that created a watertight interlocking roof, which not only directed the flow of rainwater but was easy to move from the inside to allow smoke from the interior fires to escape.

The buildings could become very large over time as sections were added and were sometimes capable of housing up to 200 individuals. As I mentioned before, the Coast Salish longhouses were the largest buildings in North America at the time, and this was due to the communal living styles that they enjoyed. The city of Seattle is actually named after Chief Sealth, who along with Chief Kitsap lived in the Old Man House near what is now Suquamish, Washington. There are different reports about the size of this house, but it would have been somewhere between 600-1000 feet in length (200-300m) and existed on a village site that had been inhabited for over 2000 years. One thing that was also unique to Coast Salish Houses is that the exteriors were often very plain and unadorned, which is a contrast to indigenous buildings constructed further north in areas of southeast Alaska, which often featured large scale murals and carvings on the exteriors of the buildings to display family lineage. Most of the adornment of Coast Salish buildings were actually inside, usually on the internal house posts and beams where only the inhabitants could see them. The carvings, paintings, and other adornments usually depicted animal guardians and totems relevant to the family groups living in the house.

Sustainable elements

I think it is important to touch on some aspects of how the Coast Salish buildings relate to our modern concepts of sustainability, because there are some striking similarities in the ways that the buildings functioned. When the time came to build a new house, sites were chose based on the relative locations of resources like bodies water, for access to food resources, and the general landscape, as houses were often built in easily defensible locations with natural advantages of height and line of sight. This is a common technique used in modern buildings as well, especially with LEED certification where access to transportation and amenities will grant points towards certification. Many houses also featured interior spaces that were dug out somewhat below ground level in order to help regulated temperature during different times of year, not unlike using geothermal loop systems for modern HVAC systems that are found in Passive House deign theory. On could even state that the structures were extremely adaptable to the needs of the occupants, simply due to the way that they were constructed. It was common to add sections and annexes on to the plank house as the size of the population inside the houses changed. The people that lived in certain sections of the houses were also the owners of the planks that crated them, often a sign of wealth, where most prestigious groups of the clan had more planks to add to the structure. This also meant that these specific planks were the responsibility of those people to maintain, and even transport when the time came to move locations in the summer and winter.

The local resources played a major role in site selection, as the main building material was the western red cedar. These trees provided long lasting, durable wood for the planks, posts, and beams that could be felled and dressed very close to the building site. Posts for the structure of the houses were dug into holes in the sand, which were filled with larger stones and boulders, creating a porous base for the post, to prevent the moisture in the ground from rotting them out quickly. This practice is still employed today with fenceposts and other wooden structural members as an insurance of longevity. The cedars also provided bark that was woven into mats that were not only used for clothing, but also used for insulation in the interior of the structures. Bark mats also served as the protective barrier against sun and wind in the summer home locations of the Coast Salish people. Freshly fallen logs were not the only source of wood, as the use of driftwood was very common, and these logs that wash up on the shores were considered gifts from nature, a practice that shows true resourcefulness in the built environment. It was also commonplace for the Coast Salish to repair planks that began to wear out, using tree sap as a fixative, and stitching cracks together with cedar bark cording. Parts of old canoes were also repurposed after their useful lives and ended up as wall and roof planks, again showing respect for the material and a resourceful nature.

Coast Salish plank houses were also multipurpose buildings in that they were not only living quarters, but also the center of spiritual ceremony connected to potlatch protocol as well as storage houses for the ever-present salmon that the people survived on. Racks were constructed in the ceiling spaces of the houses that allowed the fish to be hung and dried by exposing them to the smoke from the internal heating fires. This smoke not only cured the fish, but also kept away flies and other pests that might endanger the stability of the wintertime staple foods. Smoke from the fires was also dealt with in a clever manner, as natural gaps in the wall planks (left above grade to prevent rot) would allow some air in to keep the floor dry, and also help direct air up and out of openings in the roof. These holes could be created by simply shifting planks from the inside using a pole and replaced again if rain began to enter the building.

Because rain was a constant during the winter months, drainage became an issue that needed to be dealt with, and the Coast Salish had ways of doing this that I was surprised to learn about. The first being, which was discovered during excavations of certain sites, was that they employed a system of below-grade channels made of cedar planking on the exterior of the houses that would help to redirect water coming off the roof, along the long side of the houses, and ultimately out to the ocean. This protected the interior of the houses from becoming damp and muddy during the wet seasons. Some Coast Salish houses were also discovered to have piles of clam, oyster, and mussel shells piled up along the base of the walls to help prevent water from entering, but sill allowing some airflow into the structure.

Overall I have found it extremely interesting to examine the ways that indigenous people lived in the Salish Sea region. I think that there are some valuable lessons to be learned in the ways that they treated the land, how they developed it, and how they maintained their living spaces with a common reverence for the natural world. It gives me a little hope seeing these ideals being translated into modern sustainability efforts in the building space, and I can only hope they continue to be implemented on a broader scale.

“In that instant he saw the entire planet - every village, every town, every city, the desert, and the planted places. All of the shapes which smashed against his vision bore intimate relationships to a mixture of elements within themselves and without. The saw the structures of society reflected in the physical structures of its planets and their communities. Like a gigantic unfolding within him, he saw this revelation for what it must be: a window into society’s invisible parts. Seeing this, he realized that every system had such a window. Even the system of himself and his universe. He began peering into windows, a cosmic voyeur.”

- Frank Herbert: Children of Dune

References:

Simon Fraser University - Engaging the World. Northwest Coast Architecture - The Bill Reid Centre - Simon Fraser University. (n.d.). Retrieved May 24, 2022, from https://www.sfu.ca/brc/art_architecture/nw_coast_architecture.html

Anderson, M. K. (2009). (rep.). The Ozette Prairies of Olympic National Park: Their Former Indigenous Uses and Management (pp. 1–158). Davis, CA: National Plant Data Center. https://www.nps.gov/olym/learn/management/upload/MKAnderson_Ozette_ONP_2009-df.pdf

Wallace, C. L. (2017, April). Architecture of the Salish Sea Tribes of the Pacific Northwest - Shed Roof Plank Houses. Retrieved May 24, 2022, from http://fitchfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/FITCH_Christina-Wallace_final_web.pdf

Boome, P. C. (2015). Indigenous Architecture in the Modern World: How Indigenous Design Philosophies Can Inform Contemporary Structures (thesis). The Evergreen State College , Olympia, WA.

Trosper, R. L. (2003). Resilience in pre-contact Pacific Northwest Social Ecological Systems. Conservation Ecology, 7(3). https://doi.org/10.5751/es-00551-070306

https://www.straight.com/blogra/faces-vancouver-coast-salish-plank-houses

https://www.eopugetsound.org/articles/geographic-boundaries-puget-sound-and-salish-sea

https://www.historymuseum.ca/

https://qmackie.com/2010/04/04/old-man-house/

www.foresthealth.org